The humble bean is, intrinsically, all about potential. For anyone working in education, icons of potential are irresistible fodder. If all is right within the bean, we need not worry: it will grow magnificently, in the right conditions.

Outwardly, a bean is a very simple thing from which many good things come. Coffee; chocolate; baked beans (wrongly named but still delicious). Beans are great wholesome foods full of plant-based protein and fibre. Admittedly, they can bring some gusty after-effects, but nothing is perfect.

The bean has, for centuries and across many civilisations, been the preferred medium for learning to count. Beans are mathematical icons. The abacus would have been strung with beans. Although accountants with a tendency to pedantry are sometimes referred to pejoratively as bean counters, the humble bean is a positive symbol of accuracy and diligent learning.

In ancient Greece, beans were instruments of democracy. The practice of using beans for voting dates back to the city-states, where citizens gathered to make decisions on public matters. Voting was often conducted in a way that preserved secrecy and fairness, and beans provided a simple, practical solution. Typically, two types of beans were used: white beans for approval and black beans to reject. Citizens would cast their vote by placing a bean into a jar or urn.

The symbolism was powerful: a single bean could determine a person’s fate or influence the direction of a city-state. This system emphasized equality—every citizen’s bean counted the same, regardless of wealth or status. It was an early example of participatory governance, showing how simple objects could uphold democratic principles and civic participation. So, the bean is a symbol of democracy – respect for individual opinions – and the right to privacy. The phrase ‘to spill the beans’ comes from this ancient democratic context.

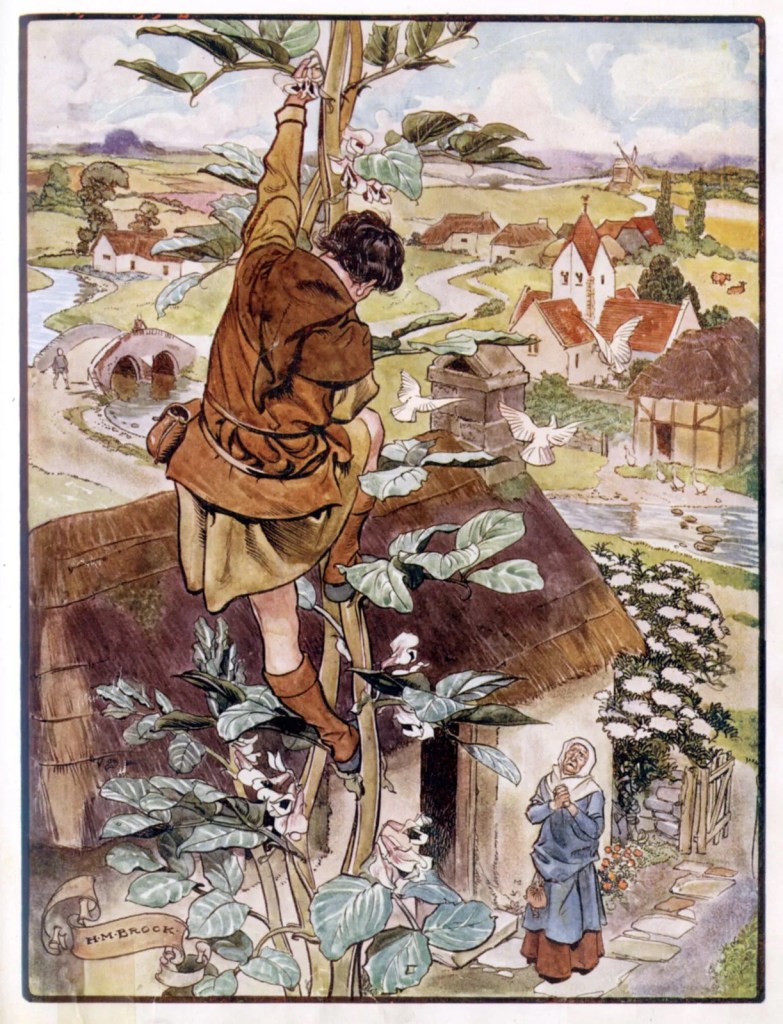

The English fairy tale, ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, is a standard in the festive Panto season in the UK. Jack, a poor country boy, trades the family cow for a handful of magic beans, much to the dismay of his widowed mother. However, the beans grow into a massive beanstalk reaching up into the clouds. Jack climbs the beanstalk and finds a road that leads to a big house, with a tall woman standing outside. He asks for breakfast and she gives him some, but warns that he might become breakfast himself if he is not careful, as her husband is an ogre with a savage appetite. While Jack is eating, the ogre comes home. The woman tells Jack to hide in the oven.

Sensing the boy’s presence, the ogre cries his famous “fee-fi-fo-fum”. However, the ogre’s wife, who has rapidly formed a liking for Jack, distracts her giant husband with a lavish breakfast of three broiled calves. Afterwards the ogre takes out some bags of gold. Counting the gold, he falls asleep. Jack creeps out of his hiding place, takes one of the bags, and climbs down the beanstalk. He gives the gold to his mother, who is very happy. They live well for some time, until it is almost used up.

Jack decides to try his luck once more and climbs up the beanstalk. Again he meets the woman at the doorstep and asks her for breakfast. While he is eating, the ogre returns and Jack quickly hides in the oven. Again the ogre suspects that somebody is there, but again his wife deceives him, allowing Jack to hide. After breakfast, the ogre asks his wife for “the hen that lays the golden eggs”. He says “Lay!” and the hen lays an egg of pure gold. The ogre falls asleep, and Jack takes the hen and climbs down the beanstalk.

Though Jack and his mother now have an inexhaustible source of golden eggs, Jack is not content. He climbs the beanstalk for the third time. He avoids the ogre’s wife, slipping into the house unseen and hiding in the wash-house boiler. When the ogre comes home, he once more cries out “Fee-fi-fo-fum”, suspecting someone is there. His wife, rediscovering her marital loyalty, suggests that the little rogue that stole both his gold and lucrative hen may be hiding in the oven. But when they find the oven empty, the ogre eats his breakfast, then asks his wife to bring him his golden harp which sings beautifully when he orders it to “Sing!”

Once the easily-fatigued ogre has again fallen into a post-prandial slumber, Jack takes the harp and starts to leave, but the harp is a talking harp, loyal to the ogre, and calls out “Master! Master!” The ogre wakes up and sees Jack running away and pursues him. Jack nimbly climbs down the beanstalk, then asks his mother to bring an axe. He chops down the beanstalk and the ogre falls to his death. Jack and his mother are now very rich. They live happily ever after, which includes Jack’s inevitable fairy tale ending: marrying a princess.

The positive spin on this story is that Jack’s adventure is all about the rewards for curiosity, courage and ambition. Jack dares to take a risk, trading the cow for mysterious and allegedly magic beans, and that bold choice leads to extraordinary opportunities. His climb up the beanstalk symbolizes striving for something greater, reaching beyond the ordinary. Jack’s resourcefulness and bravery in facing the giant suggest that challenges can be overcome with grit and determination. That small beginnings (like a bean) can lead to big outcomes.

However, the story is problematic. Should we really admire Jack’s daring gamble in swapping a cow for some magic beans? Should we actually celebrate his craft in stealing from the ogre in the land above the magical beanstalk? Or should we view him as reckless and greedy? Is the ogre, in fact, just misunderstood?

The tale rather glosses over the morality of Jack’s actions. Jack steals from the giant: gold coins, a hen that lays golden eggs, and a magical harp. While the giant is portrayed as fearsome, we don’t get his side of the story – what it’s like to be an ogre whose space is invaded and possessions taken; he’s an ogre, a giant who, we are expected to say, deserves to be outwitted because he is different and threatening – even when you break into his house and sweet-talk his wife. This tale suggests that cleverness and daring justify dishonesty, which is a problematic lesson.

We might also question the loyalties of the ogre’s wife which sway rather easily to favour the young lad from the land below. Or, we might view her as a victim too – of unhealthy masculinity of different types. Or what about the post-colonial lens? Jack, the imperial conqueror plundering treasures from foreign lands; the ogre the ignorant savage.

Should we, in fact, admire Jack? Would it not be more admirable if Jack’s success had come through integrity, not exploitation and deception. We might also worry that the story romanticizes risk without considering consequences. Jack acts impulsively, and things could have ended very differently.

Should we fear and vilify the ogre? Ever since the appearance of Shrek, ogre PR has been on the up. However, this tale suggests that anything non-human and strange is not to be trusted. Even if it’s minding its own business when you come bundling into its domain.

Now, you might say, it’s just a fairy story – a Christmas panto – and I’m being a boring killjoy labouring over the meaning of the tale. But… the stories we tell shape the way view the world. The accounts we accept (fictional or real), without critical reflection become our world; the heroes we promote and the villains we push away.

Later versions of this fairy tale add some previous villainy to the giant’s rap sheet – eating oxen and little children – to make us feel more comfortable with Jack’s actions. Although Jack is essentially a vigilante on the make, it seems much more acceptable that he robs and kills an ogre who has himself been wicked. But, in the original, he is really targeted for being big, different, well-off and from another land. Not the best justification for stealing his livelihood and ultimately knocking him off.

Jack’s tale might urge us to dream big and take a few risks. No bad message as we start a new year, I suppose. Reflecting with a more critical eye, it may also suggest that we temper our ambitions, and pursue them with a more measured and collaborative spirit, with honesty and responsibility. Good things come through effort as much as through daring.

Surely, it is better to accomplish our aims through collaboration and hard work, rather than shortcuts and deceit. In climbing our various ‘beanstalks’, we should pursue our goals boldly, but with fairness, kindness and respect for others.

In other words, just as ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz’, being fully human means being fully humane beans.

Notes:

This letter was written on 6 January (The Feast of Epiphany, a time of gifts). It was a kind of epiphany to learn that there’s a day set aside especially for celebrating the bean in all its many, simple glories. 6 January is also National Bean Day.

The iconic advertising slogan ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz’ was created in 1967 by copywriter Maurice Drake. There are more than 57 Heinz varieties, but founder Henry J Heinz, who formed the company in 1896, thought the number 57 had a good feel to it – and it combined his and his wife’s ‘lucky numbers’.